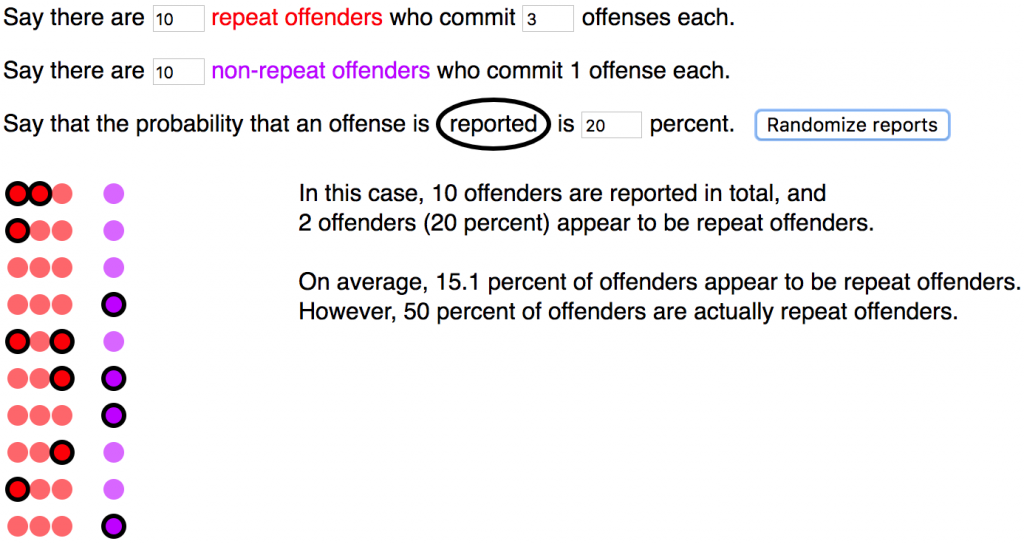

Co-authored with Ian Ayres and Jessica Ladd. In this paper, we explain how drawing naive conclusions from “act sampling”—sampling people’s actions instead of sampling the population—can make us grossly underestimate the proportion of repeat actors. We call this “act-sampling bias.” This bias is especially severe when the sample of known acts is small, as in sexual assault, which is among the least likely of crimes to be reported. Virginia Law Review Online 94.

The widget for this paper, written in Javascript using D3.js, is available here.