4.3 Octave Granite Lithophone

Michael Chwe, September 2011

This summer I made a lithophone out of granite

tile with a range of

4.3 octaves, going from A3 to C8 (essentially the top half of the piano). A lithophone is a mallet

instrument (such as a marimba or xylophone) in which the bars are

made

out of stone. Some of the earliest musical

instruments are lithophones.

Click here to hear an excerpt of Monograph

IV by Richard

Gipson played on the lithophone (by Hanyu Chwe). To hear its

entire range played by different mallets click on one of the following

links (mallets with hard plastic

heads, wound cord heads, brass heads, rubber heads).

Total cost of materials was roughly $300 ($200 for the granite bars,

$40 for the aluminum

U-shaped channels which support the bars, $10 for the wood

supporting the aluminum channels, and $50 for the folding black metal

stand which supports it all). The stone-cutting saw

used for the project cost roughly $100, so it was relatively

inexpensive considering that most mallet instruments with a 4.3 octave

range cost well over $2000. No special skills were

required. I had never cut stone tile before, but it was not

difficult to learn. Most of the work (around 10-15 hours) went

into cutting and tuning the granite bars. The lithophone is 6 feet (183 cm) wide,

height-adjustable, and easily portable.

Bars

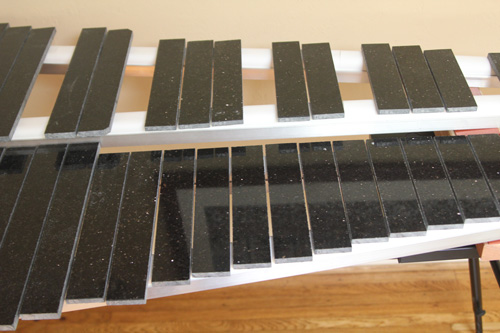

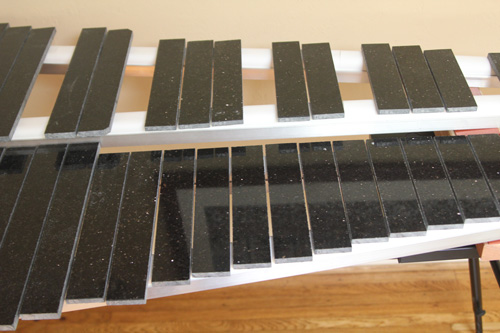

I used "Black Galaxy"

granite (it is black with silvery specks) ordered through Bourget Brothers (a local stone

shop) because it produced a good sound and was relatively low

cost. I cut the bars

2 inches (51 mm) wide. The length of the bars range from 4.7

inches (119 mm) long to 22.5

inches (571 mm) long (for a

complete list of dimensions, click here).

I cut the shorter bars (from E5 to C8) out of 12 inch by 12 inch (12 x

12) square tiles, which were roughly 10mm thick and cost around

$10 each. I cut the longer bars (from A3 to D#5) out of 18 inch

by 18 inch (18 x 18) square tiles, which were roughly 12 mm thick and

cost around $25 each. I used roughly 6 of the 12 x 12 tiles and 5

of the 18 x 18 tiles.

Tuning the bars

I tuned each bar by

hand, removing small amounts off the ends of the bars until the correct

pitch was reached. I used an Korg OT-12 electronic

tuner (now replaced by the OT-120)

to reach the correct pitch. Tuning by hand is required because

individual tiles vary (in thickness for example) which affects the

pitch (thicker

tiles have higher pitch). With the tile saw, it is easy to

grind off very small "slivers" off the bars (0.5 mm or even less) and

tune each bar to within 10

cents (10 percent of a semitone) of the correct pitch.

A tile saw is really a grinder: a rotating metal disc with embedded

diamonds grinds a roughly 1 mm groove in the stone. The disc

rotates in a pool of water, which gets you and everything around you

wet. It is definitely something to be done outdoors. But it

is not difficult or unsafe (I used a full

face shield, which is more comfortable than safety glasses, a simple

respirator, and ear

protection). I was worried about breathing in granite dust

and getting hit in the face with bits of stone, but the process is wet

enough that this is not an issue. You end up with a lot of

granite mud. Tile saws can be large and expensive, but the small MK

Diamond MK-145 was more than adequate for the job.

The main difficulty in tuning the bars was that the electronic tuner

(and the Korg OT-12 is supposed to be one of the best) often had

difficulty locking on to the correct pitch, perhaps because bars have

unusual overtones and also because their sound does not sustain very

long.

Supporting the bars

One novel aspect of my design is how the bars are supported. In

my lithophone, the bars are supported by an arch of paper, which is in

turn supported by aluminum U-shaped channels, 2 inches (5 cm) wide and

1 inch (2.5 cm) high.

One problem with paper is it eventually sags, as shown in the channel

on the right in the photo above. This is especially a problem for

the heavier lower-pitched bars. To fix this problem, I first put

a piece of rigid plastic inside the channel to

prevent the ends of the paper, the "base" of the arch, from being

pushed inward away from the edge, as shown in the channel on the left

above. Second, I used two or three sheets of paper for greater

support. I ended up using 110 lb cardstock

(what index cards are made of). I cut a 8.5 inch by 11 inch

sheet in half lengthwise to get a 4.25 inch by 11 inch sheet. For

the plastic inside the channel, I use PETG plastic, 0.020 inch thick, cut to

2.5 inch by 12 inch sheets. For the higher pitched bars a single

sheet of paper works fine, but for the lower pitched bars as many as

three are necessary to prevent sagging.

I was inspired to use paper arches by the book Musical

Instrument Design by Bart Hopkin, which suggests supporting bars

with balloons. Since balloons are such low mass, they do not

dampen the bar's vibration, regardless of where the bar is placed on

the balloon, and the balloon surface provides more vibrating area,

improving the sound. I experimented with air

pillow bags (a common packing material) which also sound great, but

like balloons deflate over time. Paper arches turn out to be

similar to balloons, amplifying the sound with little damping (for

example, whether a bar is supported by its nodes or not does not affect

the sound). A

video explaining the design is available here.

Supporting the channels

The aluminum channels are supported by wood 2 x 4 lumber, as shown

below. The left-hand wood support is a 15 inch board attached to

the top of a 30 inch board, and the right-hand support is an 8 inch

board attached to the top of a 16 inch board. Glued to the top of

the boards are sheet rubber, to maximize friction with the aluminum

channels (sheet rubber is also glued to the ends of the aluminum

channels to keep them from scratching things).

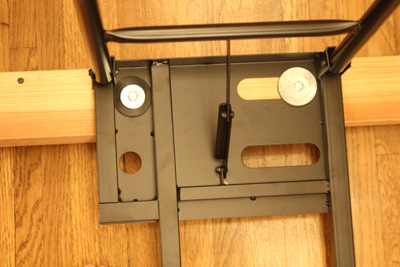

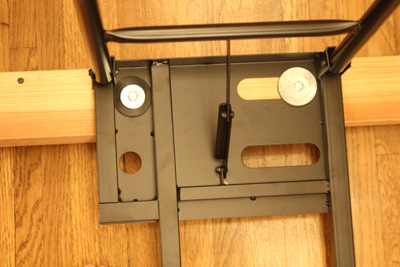

The wood supports are in turn attached to an inexpensive commercial

keyboard stand (model KS7150 made by On-Stage Stands). Wood

screws, large "fender" washers and large rubber washers are used, as

shown below.

Adjustability and portability

This lithophone design is very adjustable. The granite bars can

be placed anywhere on the paper arches. The aluminum channels can

be placed anywhere on the wood supports. With the aluminum channels, one can

also easily use arches made of different materials,

such as plastic, mesh, or metals. The height of the keyboard stand

itself can be adjusted by extending its legs (admittedly not as

convenient as a crank, as in this

design). To

transport the lithophone, the granite bars and aluminum channels can be

carried separately and the keyboard stand can be collapsed and

folded.

Disadvantages

The main disadvantage of the

design is that since the bars and channels are not attached, a large

sideways shock could cause them to fall. The granite bars can be

surprisingly fragile; I tossed the C#4 to the grass from a height of

one foot and it broke into two pieces, and thus I had to make a new

one. The lithophone also must be picked up by the legs to be

moved, if you don't want to remove the bars first.

Experimentation

I tried granite at first,

but many kinds of stone (and ceramic tile, which is fired from clay and

can be much cheaper) sound good and could be tried. For me,

getting granite in large enough lengths was the main constraint on the

lithophone's range. I had to cut the larger bars out of the

diagonal of a 18 x 18 tile. I could have made a G3 bar and G#3

bar, extending the lithophone's range to 4.5 octaves, but each bar

would have required buying a single 18 x 18 tile, which seems

wasteful. I once ordered a 24 inch by 24 inch tile, but it was

much thicker (roughly 0.75 inch thick) and thus would not have

necessarily reached lower pitches even at much longer bar

lengths.

Instead of simply a longer bar, another possible method for lowering

pitch, as used in the wood bars in marimbas, is to hollow out or cut a

notch in the middle of the bar, reducing the bar's stiffness. I

haven't tried this yet. When I cut bars diagonally out of square

tiles, I ended up with trapezoidal (not rectangular) bars, which often

sounded very good, perhaps because they might have different overtones

than rectangular bars.

Many mallet instruments have resonator tubes to enhance the

sound. I haven't tried this yet but resonator tubes would be

compatible with the paper arch support design here.

Musical qualities

Notes played together on the lithophone sound great as long as they are

close intervals, within an octave. Triads sound great too.

However, tenths (an octave and a third), elevenths (an octave and a

fourth), and twelfths (an octave and a fifth) sound bad because the

first overtone of a vibrating bar is a sharp eleventh (octave and a

fourth), as explained in Bart Hopkin's book.

Even octaves on the lithophone can sound strange.

Here is the lithophone next to a M250 Musser marimba (adapted to be height-adjustable) which

also has a 4.3 octave range but is an octave lower.

Questions and comments

If you have any questions or other

suggestions, please contact me at michael@chwe.net.

Thanks!